Stuart Hall argues that popular culture

is a site defined by struggle – for and against the dominant culture “It is the

arena of consent

and resistance”.

BACKGROUND

It is our use of a pile of bricks and mortar which makes it a 'house'; and what we feel, think or say about it that makes a 'house' a 'home'.

— Stuart Hall

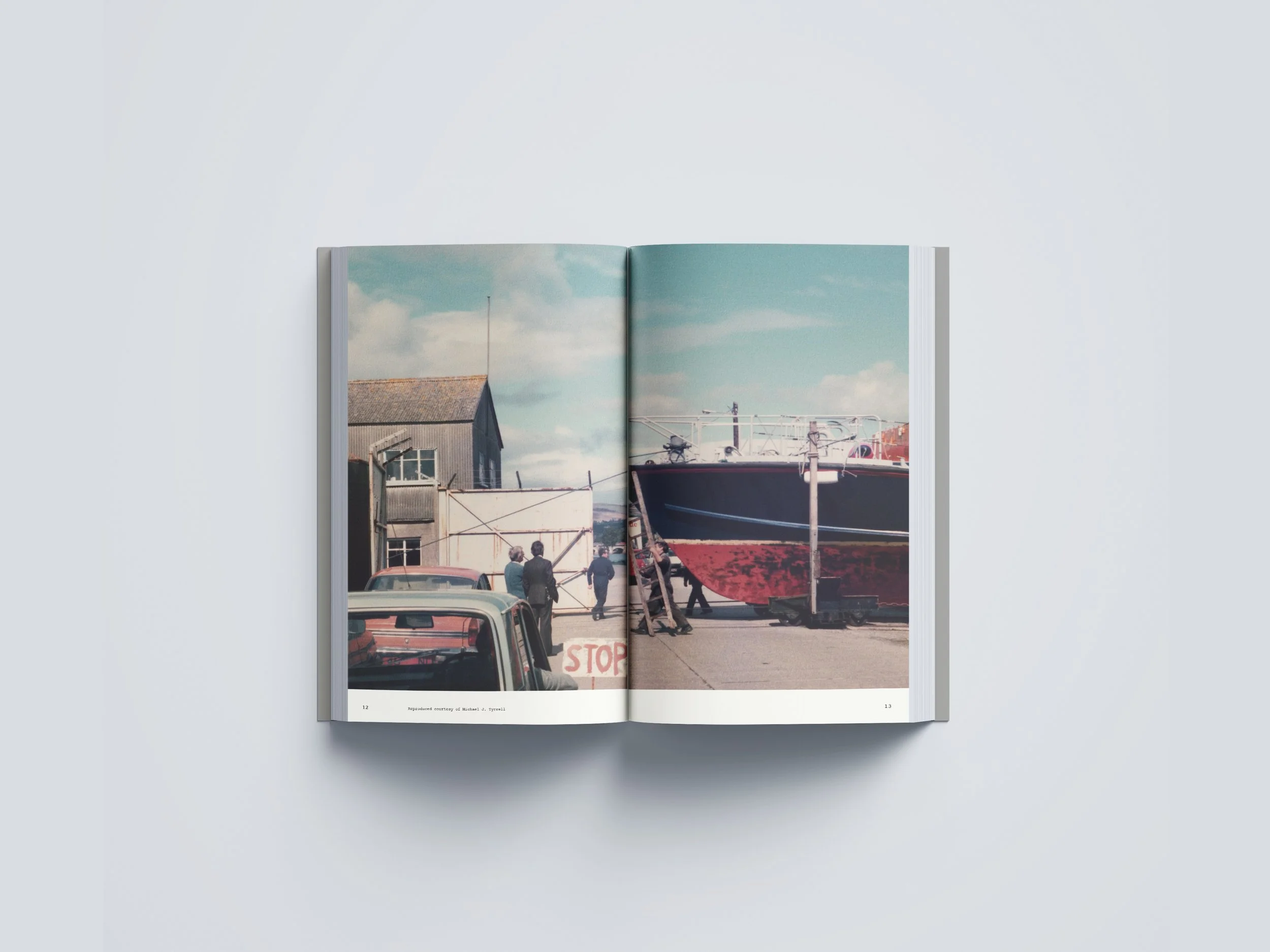

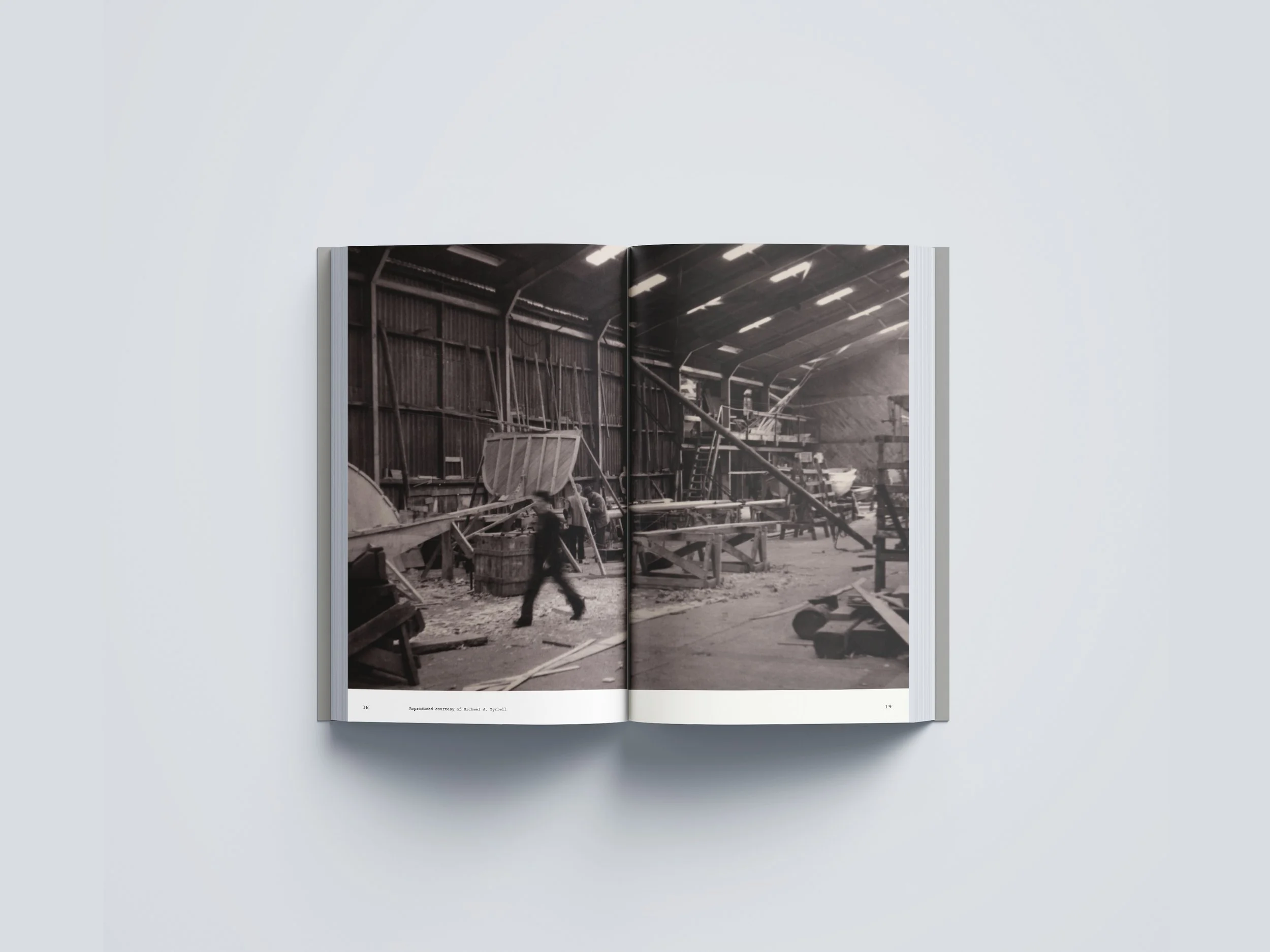

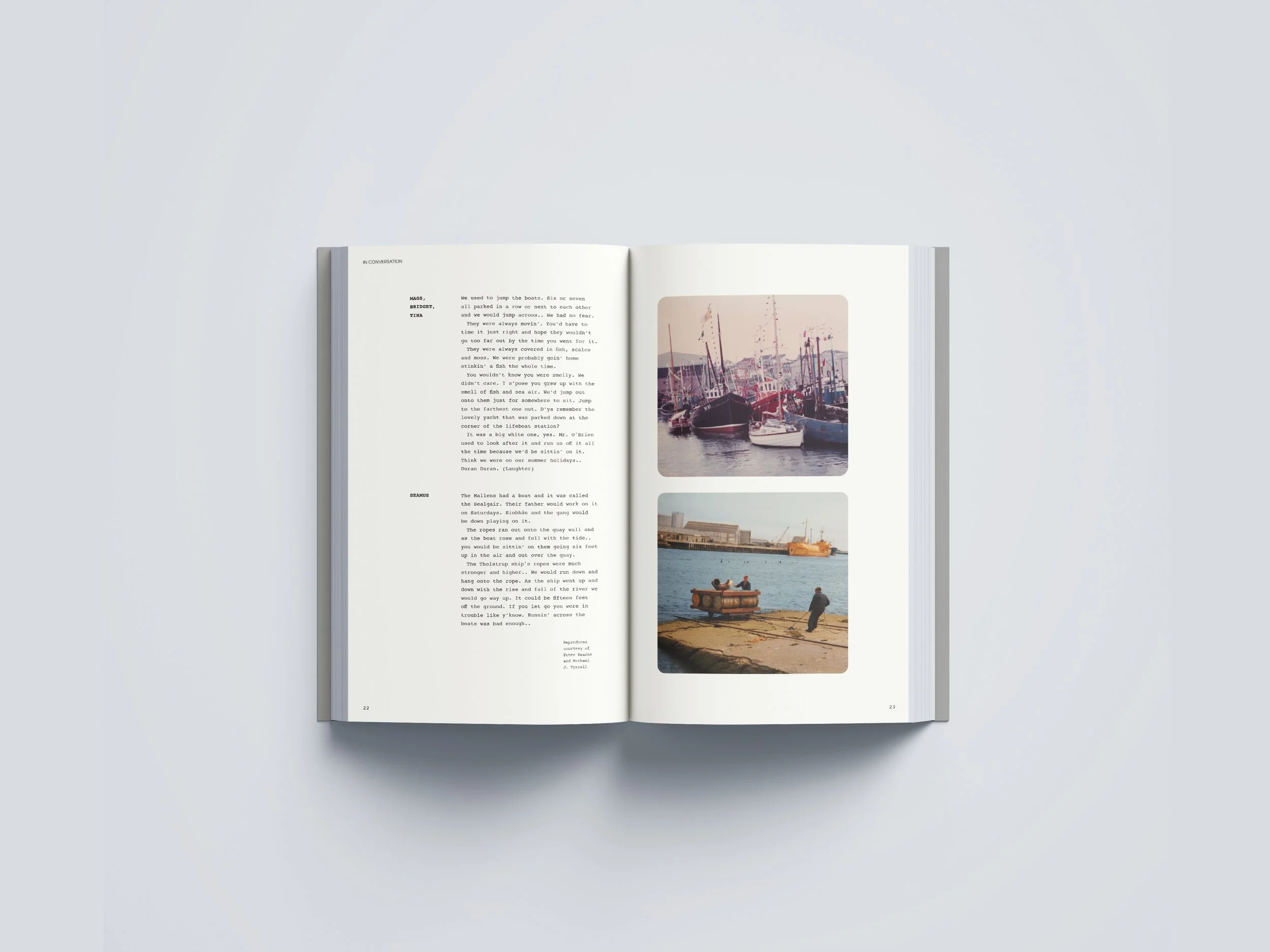

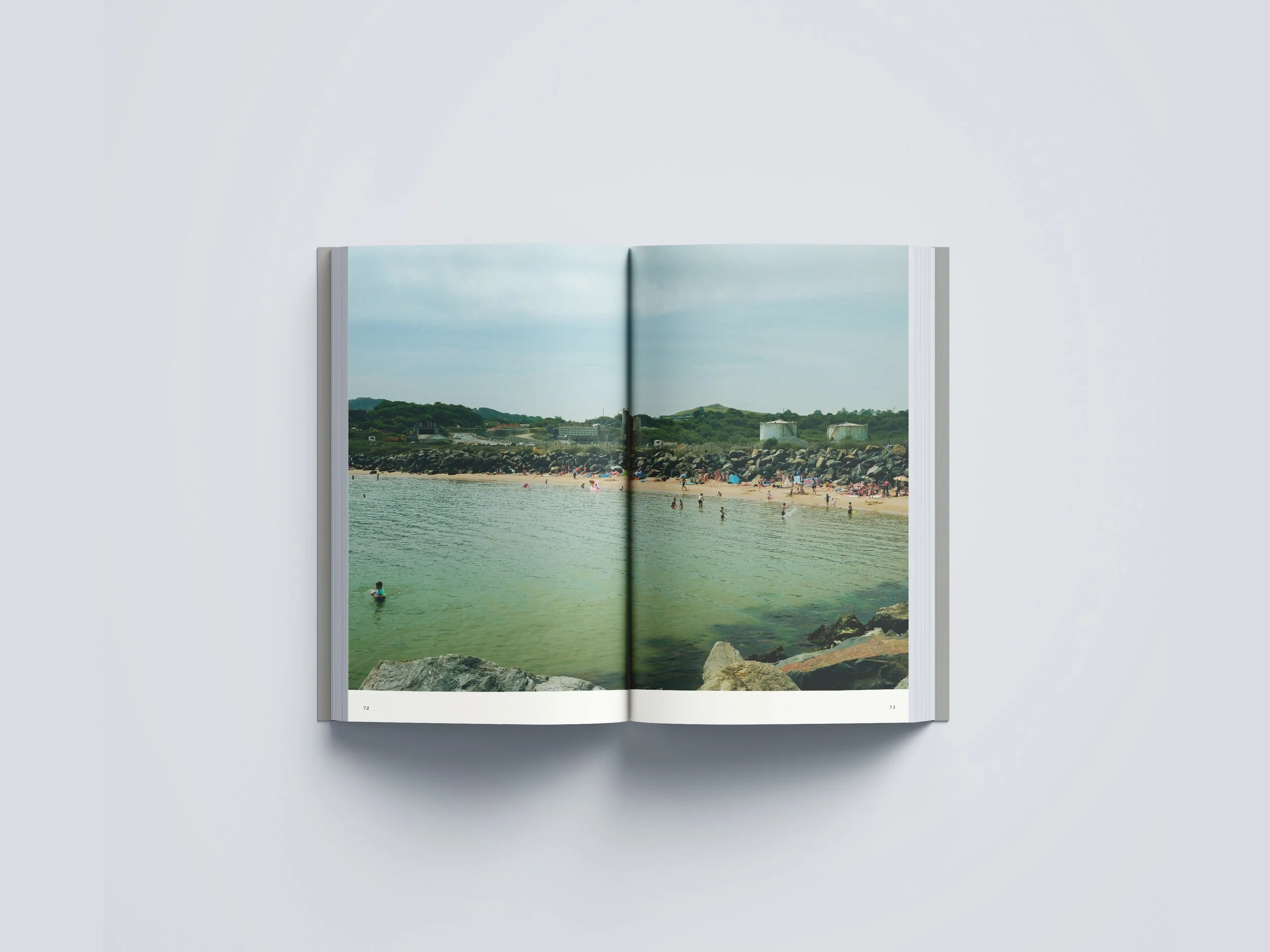

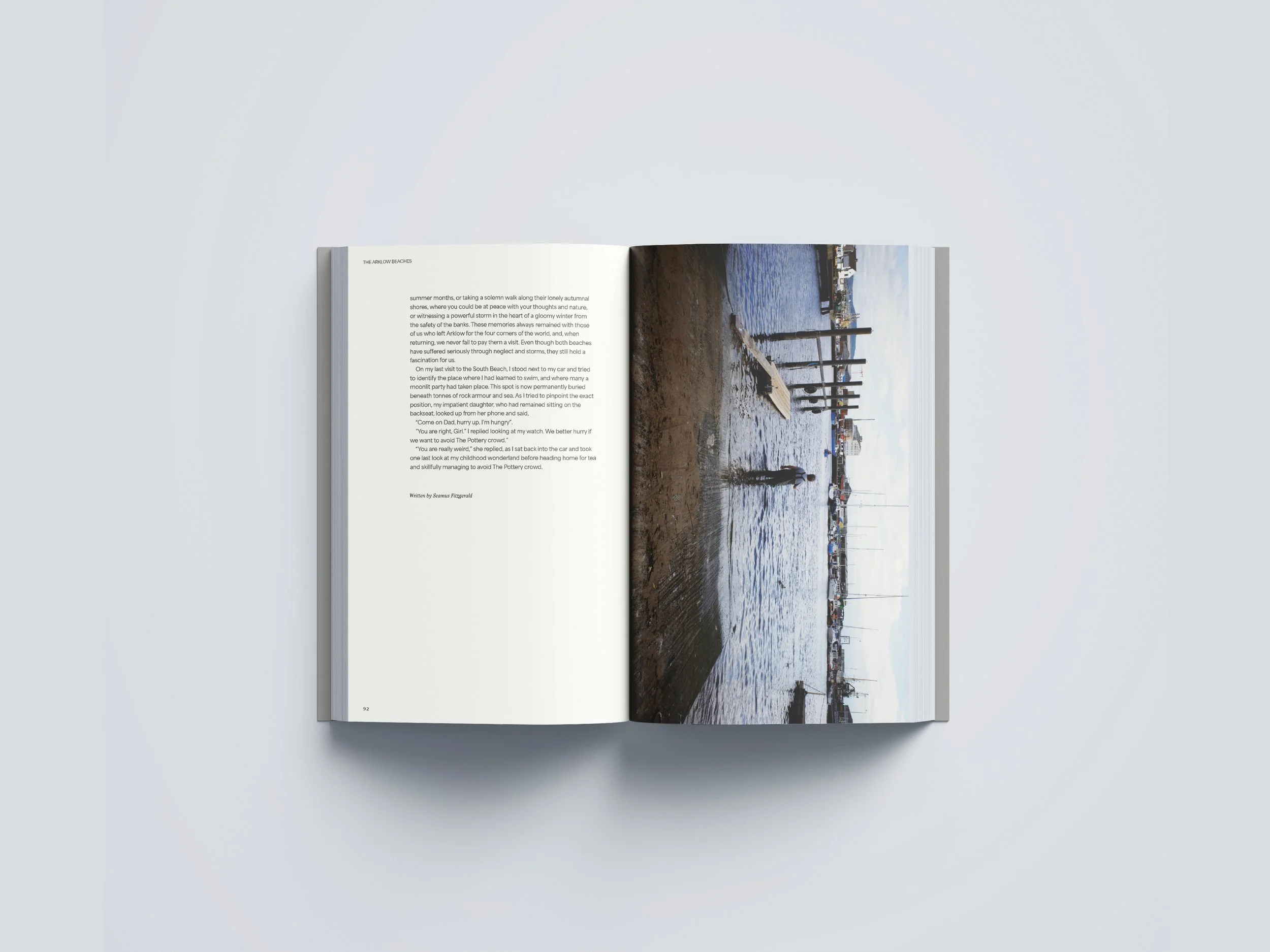

Arklow was arguably the most industrialised town in Ireland. The harbour – within the place-name of ‘The Fishery’ – served as the epicentre of community and industry for the town.

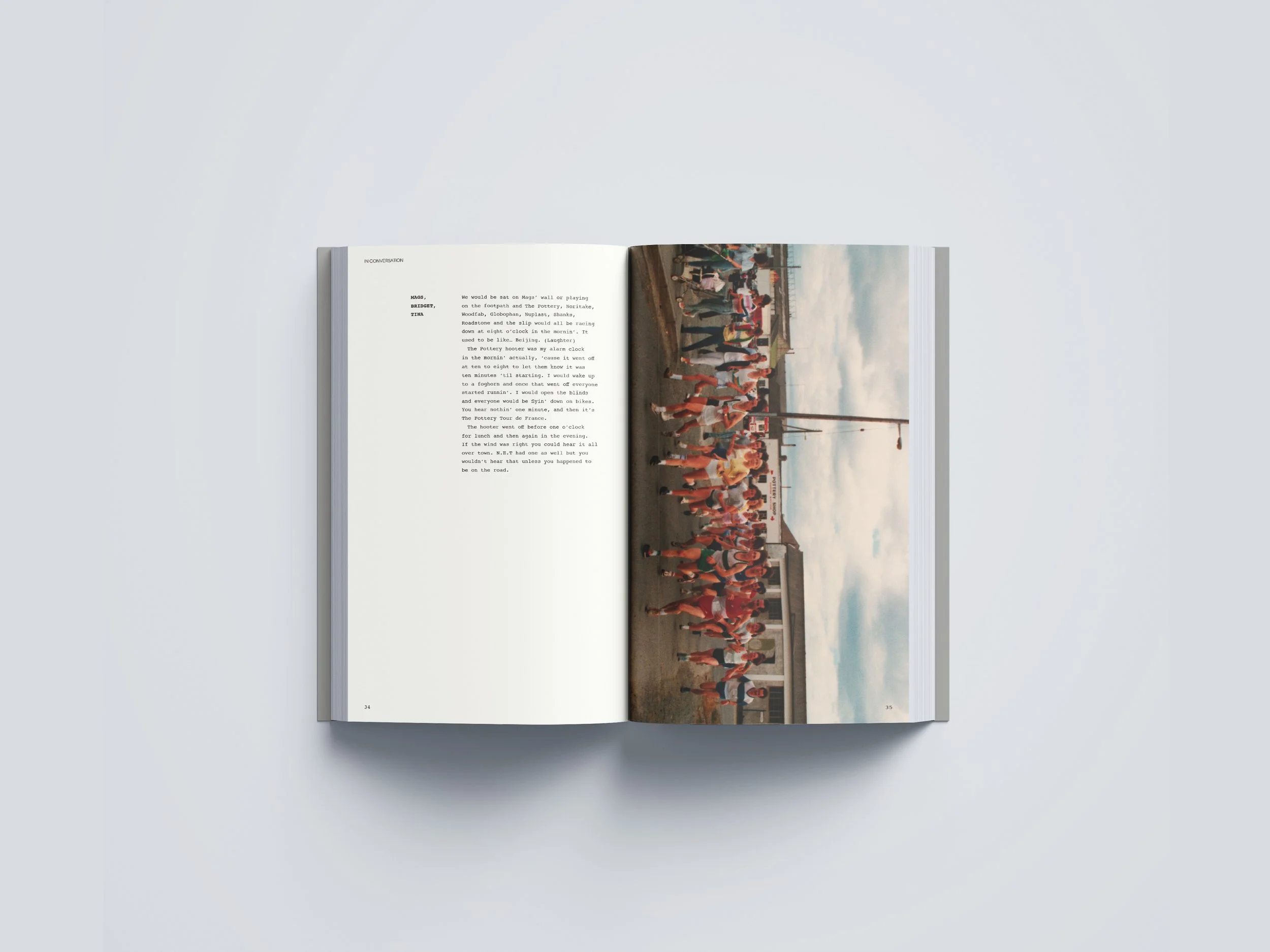

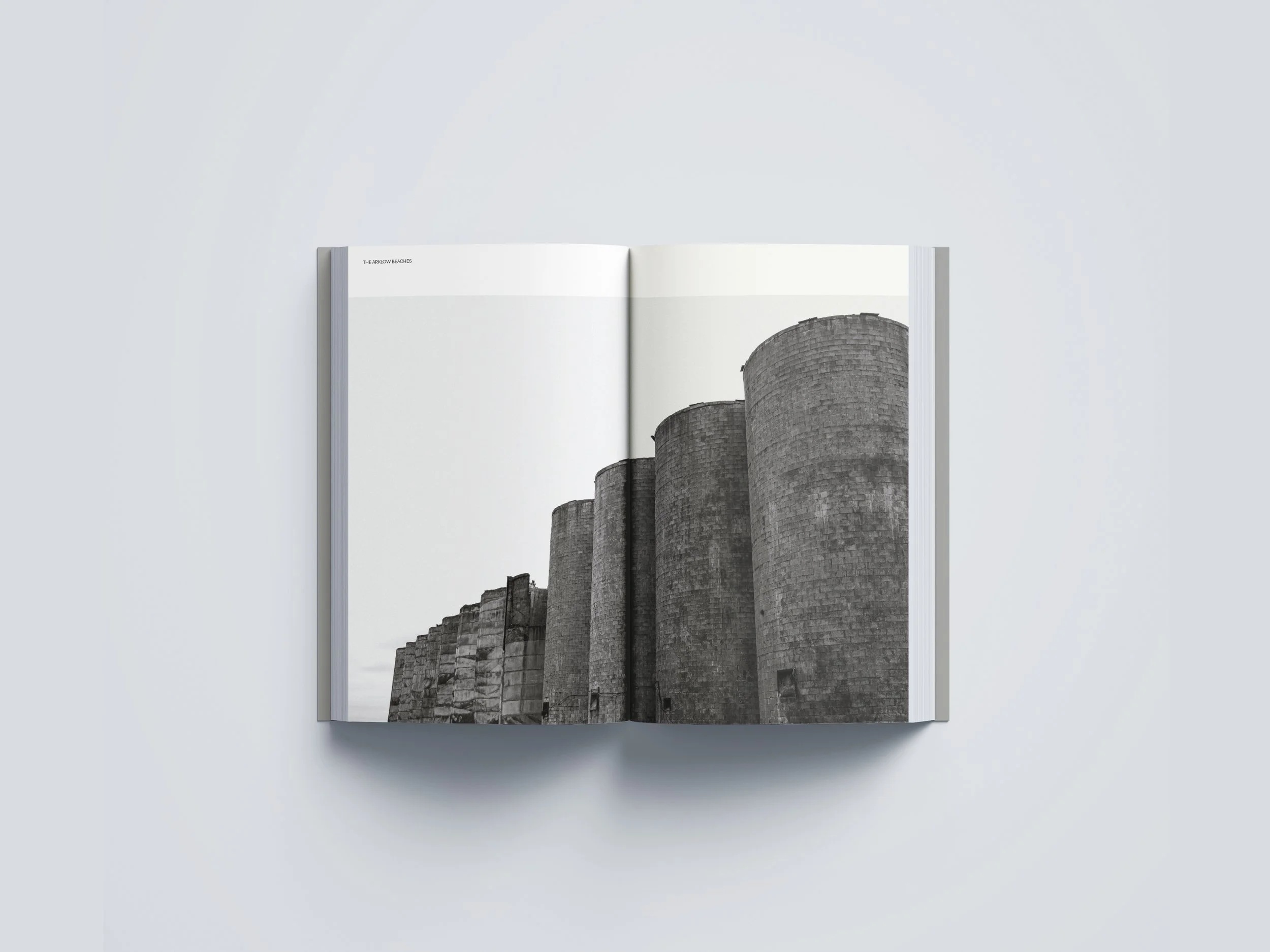

Industries such as Nitrigin Éireann Teoranta, Arklow Pottery, Nuplast, Shanks, Roadstone, Noritake Porcelain, along with a long custom of boat building and fishing, provided a means of leisure, as well as labour. Since the official closing of Arklow Pottery in 1998 – the remains of terminated industries and the culture that came with it lay derelict.

Presently the representation of culture is embodied through the Arklow Town coat of arms which is used as an apparatus for communicating identity. The adoption of a Viking ship to convey cultural and economic industry was given precedence for its romanticised ideology.

While there are strong grounds for the name ‘Arklow’ deriving from Norsemen and boat building dating back to the 11th Century, the reliance on Vikings at a time of mass media and popular culture leads me to believe this was an assertion of region branding. The intention was to capitalise on these ideals for tourism trade, aiding in the towns branding strategy.

Although the adoption of the crest was initially intended for local authority and tourism, it has since been mobilised for parades and community programmes since the nineties. The representation of Arklow is consistently negotiated between the subordinate and dominant cultures - but under no circumstances to ever be “sullied” by workwear. This dominant ideology distorts meaning through overdetermined signifiers and places limits on the cultural production of the town and place-name.

Through embodying contradictions, hegemonic processes are transformed into lived experiences. The naturalisation of Viking ideology makes

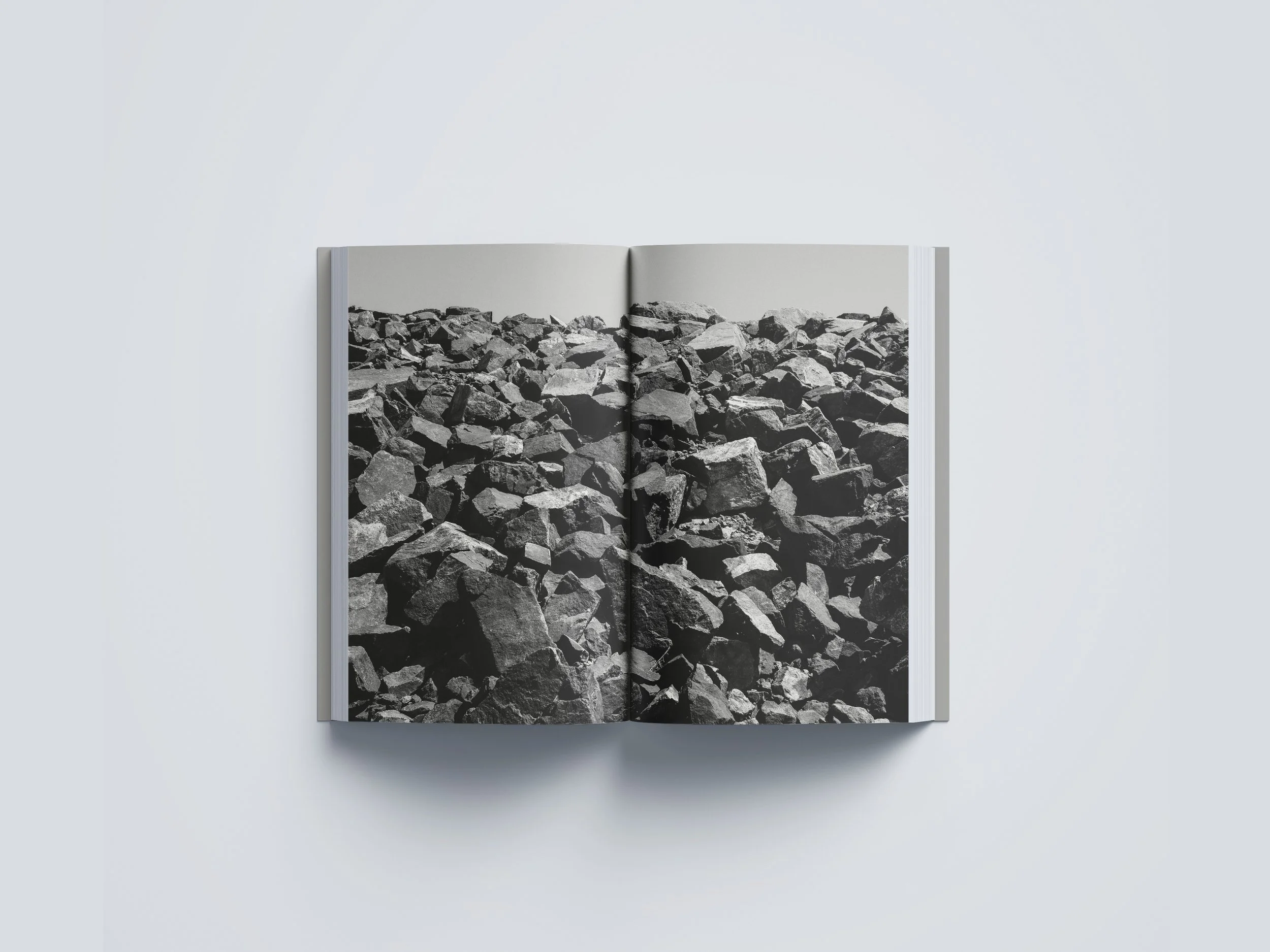

the area inaccessible for new meaningful productions of knowledge which creates a sense of shame around the now derelict polluted surroundings.

DIALECTIC SHORT FILM

According to cultural theorist Stuart Hall, culture can be defined as a space for interpretive struggle.

I was an active participant in grassroots sports. This facilitated a space for a universal language in which community can work towards one common goal. Drawing upon Foucault’s claim that individuals resist fixed identities and submission through exercising the body as a primary site of power, I relied on my position of occupying the space of dominantly masculine sports and using sparring as a tool in the process of my own identity-making.

Hall proposes that culture is simply ‘experience lived, experience interpreted and experience defined’. Through the medium of film, this dialectic cultural struggle reveals commonalities, similar practices

and values on the ground in which they are transformed.

This dialogue between cultural participants enables the viewer to determine co-existing shared meanings. By narrowing the gap between generational cultural responses, this demonstrates the production and exchange of reciprocal cultural practice. The viewer can see that they are interpreting the world from a similar reference point.

Sounding for the detection of fishing shoals and the mapping of sea-beds began to make significant progress with the introduction and development of recording instruments.

With the intention of documenting the effect the location has on the relationship between leisure and labour, the concept of an echo-sounder has the ability to challenge the finite representation of the harbour. In this case, culture is not homogenous nor a closed system.

The footage of maritime events alongside boxers creates a shared conceptual map and language of the culture we inhabit. The application of abstracted home footage combines a “theatre of struggle” – mapping the bed of the harbour through leisure and labour and negotiating the false dichotomy that comes with it.

The film demonstrates that new and probing possibilities of creative construction are permissible in the harbour while mapping the continuing cultural activity of the town.

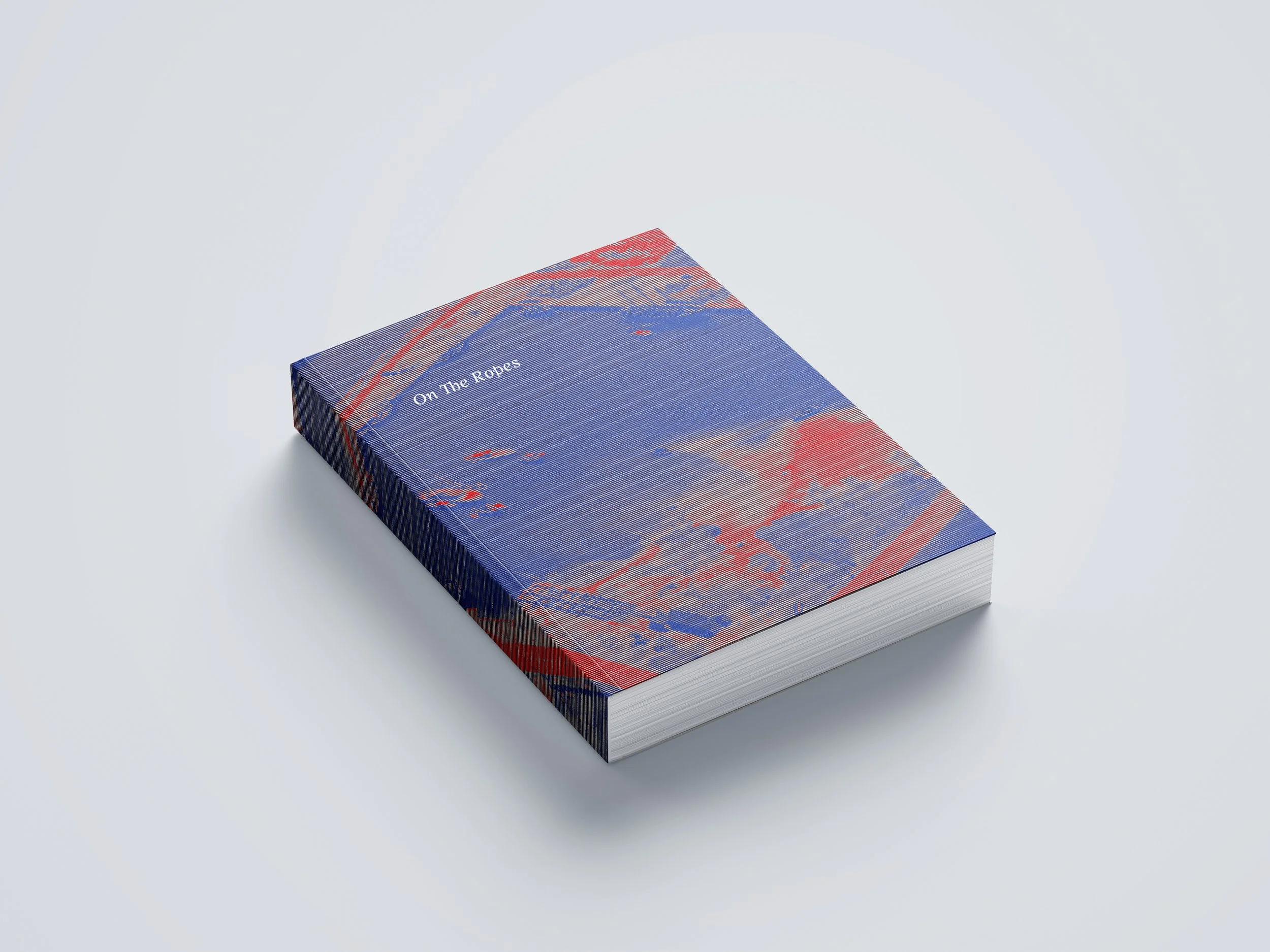

ON THE ROPES

This project consists of a multimodal outcome, comprised of a publication and moving image piece. Both pieces were commended in two categories of the IDI Graduate Design Awards. The film was commended

in the Moving Image category and the publication in Design For Sustainability.

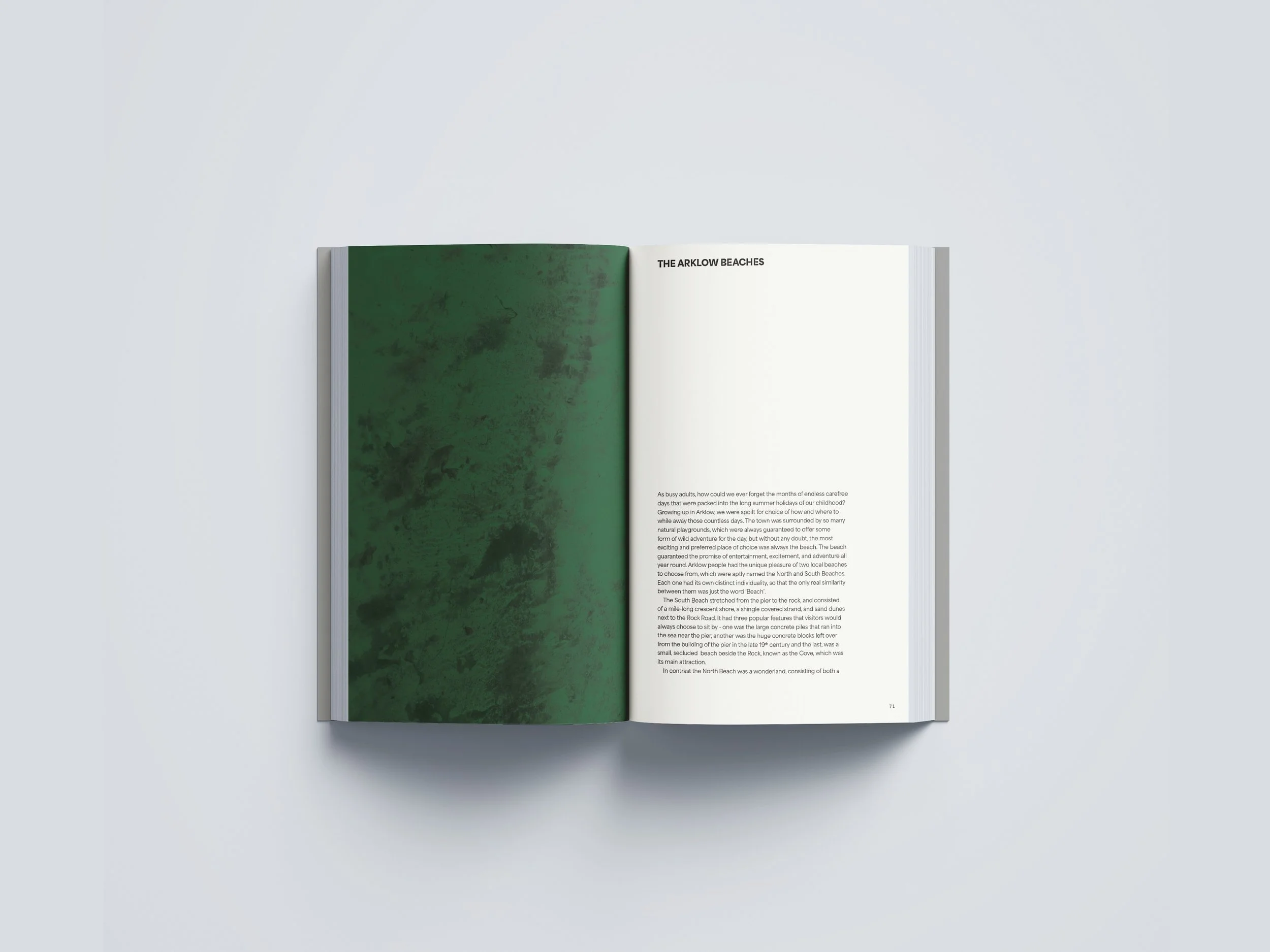

The aim of the publication is to challenge the Viking representation of a post-industrial landscape by interrogating and documenting the cultural practice of ‘The Fishery’ in Arklow.

The Fishery has been unstable for decades due to the appalling working conditions of the harbour, natural erosion of the area and the pollution of cyanide and acid in the river caused by local industries that were mostly government and foreign owned.

Subsequently, leisure was important in giving meaning to the place-name and coping with the realities of the environment.

The recent Viking representation attached to the area acts as a veil of appropriate representation, which in turn, creates a sense of shame around the now derelict and polluted surroundings.

In reference to cultural theorist Stuart Hall, culture can be understood as the shared meanings of a society. Therefore, cultural practice is the exchanging of these meanings, through participants, who produce and give value to a place or objects. These meanings and values rarely have one fixed interpretation.

The publication seeks to ground the cultural practice of the area through testimonials, essays and home photography. This provides an ethnographic approach to visualising cultural practice which gives a framework of intelligibility that will make active participants in breaking down the distorted cultural image of the town.